Prince’s Super Bowl Halftime Show: The Night He Made It Rain Harder

Prince arrived at Dolphin Stadium on February 4, 2007, to play the biggest stage in American entertainment—and the weather had other plans. The first Super Bowl ever played in steady rain turned the field into a slick, reflective canvas, the sort of curveball that makes producers blanch and legends grin. Before kickoff, word spread of a backstage exchange that would enter pop-culture lore: told about the worsening downpour, Prince coolly asked, “Can you make it rain harder?” In a business famous for controlling every variable, he welcomed the one thing no one could control—and made it part of the show.

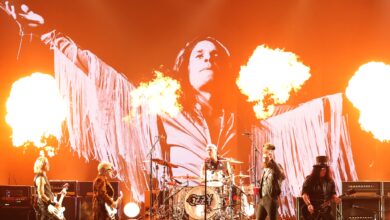

Super Bowl XLI paired the Indianapolis Colts and the Chicago Bears, but by halftime the night belonged to another contest: Prince versus the elements. More than 74,000 poncho-clad fans ringed a field where a giant, glowing stage—cut in the shape of the artist’s “love symbol”—would be rolled out by hundreds of volunteers like a neon ship docking in a storm. It was a design choice both grand and risky; that glimmering surface becomes treacherous when wet, and now it was a skating rink with power cables. As crews hustled, they weren’t just setting a stage—they were betting on a performer who loved high-wire acts.

The build-out alone was a spectacle. Seventeen interlocking pieces formed the love-symbol platform, lit along the edges and engineered to deploy in minutes between game action. Volunteers rehearsed the maneuver like a pit crew; on the night, they threaded the pieces together with clockwork accuracy while rain sheeted down and cameras counted backward. You could feel the broadcast director’s heart rate in the cutaways—this was live television at its most combustible, and the star hadn’t even appeared yet.

When he did, Prince rose through a hydraulic lift, turquoise suit blazing against the ash-gray sky, scarf tied tight against the wind. The band hit a rumbling nod to Queen’s “We Will Rock You,” fireworks strafed the rain, and any doubt about weather-related dampening evaporated. He slammed into “Let’s Go Crazy,” his Strat snarling as if delighted by the extra static in the air, while the crowd roared through a call-and-response that felt less like nostalgia and more like incantation. The famous Super Bowl halftime tightrope—twelve minutes to be universal—suddenly looked like home turf.

Then came a left turn that explained why booking Prince was never “safe.” He threaded a medley of “Baby I’m a Star” and “1999” with Florida A&M’s Marching 100, a collaboration that turned the soggy field into a gleaming parade route. The marching band, accented with illuminated tape for television pop, added brass swagger and pageantry—an American spectacle layered over an American ritual. In a lesser performer’s hands, it could have felt like crowd-pleasing filler; here, it felt like another brushstroke in a fast-moving painting.

Just as viewers settled in for a hits-only victory lap, Prince pivoted into a different register: covers. He laced Creedence Clearwater Revival’s “Proud Mary” to Bob Dylan’s “All Along the Watchtower,” vaulting from swamp swing to apocalyptic folk-rock with the kind of tonal command that says, “I know these songs’ bones.” There’s a confidence in treating American canon as living clay, and he had it to spare. The sequence wasn’t just a medley; it was a thesis about lineage—how a Minneapolis original could be a perfect vessel for the country’s jukebox history.

And then the most eyebrow-raising choice of the night: the Foo Fighters’ “Best of You.” On paper, it’s a post-millennial stadium roar miles from Prince’s purple kingdom. On the field, he treated it like a gospel dare, wringing out its “Is someone getting the best, the best, the best of you” refrain until it felt as old as call-and-response itself. The decision, remembered as both audacious and generous, expanded the halftime show’s vocabulary—this wasn’t a promo reel; it was a living mixtape, stitched for television and thunderclouds.

The rain, meanwhile, refused to become background. Camera lenses beaded; lights refracted in sheets; the stage shone like wet chrome. Where many artists might shrink their movements to keep footing, Prince leaned into theater—wide stances, saber-thrust chords, dancer sharpness from The Twinz punctuating the frame. The aesthetic accident of the storm became a design element, making every silhouette and flare feel deliberately cinematic. The show stopped trying to ignore the weather and started collaborating with it.

Production anxiety was not imagined. Mylar-slick surfaces plus high heels plus live electricity equals a producer’s worst dream, yet the team’s safety calculus and Prince’s intensity coexisted. Accounts from inside the truck describe the nervous math—angles, cables, lightning graphics versus actual lightning—and the calm at center stage. It’s telling that the moment most viewers remember as “effortless” was the result of dozens of people juggling variables in real time while trusting a headliner who thrived on variables.

Then came the closer, and with it the myth. A translucent screen rose, backlit to throw a giant shadow across the rain, and the opening chords of “Purple Rain” curled out like a weather report rewritten as hymn. The silhouette—guitar neck tilted, body a calligraphic stroke—looked like a stadium-sized puppet show for the gods. Because the storm was real, the purple flood of light turned the drizzle into falling ink. The title had never felt so literal or so earned. People still argue about “best halftime ever,” but few argue about best ending.

In the truck, producers had to balance poetry with pragmatism—handhelds dodging spray, cranes finding clean arcs through the mist, switchers choosing lenses that could tolerate droplets without smearing the picture. The fact that millions at home experienced the moment as pure magic speaks to a crew that turned occupational hazard into visual texture. Slick fields rarely make for great live television. This one did because a showman and a set of pros decided the weather wasn’t an obstacle but a collaborator.

Context matters here. In the years after the Janet Jackson controversy, the NFL had gravitated toward legacy acts perceived as “safe,” an approach that risked trading surprise for predictability. Prince honored the booking brief—iconic, broadly beloved—while detonating any notion of safe. By splicing Queen, CCR, Dylan, and the Foos into his own catalog, he reminded a massive mainstream audience that showmanship means conversation, not recitation. He didn’t just play a halftime; he reset the format’s ambition.

The audience numbers underscore the stage: a national TV rating north of 40 and an estimated viewership cresting past 90 million, with 140 million cited for the broader broadcast reach. That scale often flattens nuance—big rooms reward broad strokes—but Prince found intimacy at planetary size, delivering close-up emotional beats inside a wideshot circus. The game’s headline was football; the night’s memory trace was twelve minutes where pop, rock, funk, and weather formed a temporary band.

Critical consensus arrived fast and never really wavered. Contemporary write-ups called it one of the greatest halftime shows ever; retrospective lists routinely keep it near or at the top. Decades of Big Game spectacles later—drones, sky-hooks, augmented reality—people still cite a turquoise suit, a love-symbol stage, and a rainstorm you couldn’t script as the pinnacle of the form. The more the production arms race escalates, the more that night reads like a counterargument: give a genius a guitar and real weather, and watch television become cinema.

Even the set list tells a story about American music. Start with a Queen stomp to gather the tribe; sprint through Minneapolis funk; detour into the Delta via Fogerty; scale Dylan’s watchtower for apocalyptic flavor; test a modern rock anthem for spiritual voltage; and close with a signature that sounds, under those clouds, like destiny. In twelve minutes, he mapped a lineage, placing himself not outside it, but right in the bloodstream. The rain didn’t wash the lines away; it underlined them.

Ask production veterans what they remember and they’ll point to that pre-show line—“Can you make it rain harder?”—because it captures the whole evening’s nerve. Entertainment often promises control; art often requires risk. Prince understood that sometimes the most controlled choice is embracing what you can’t control and building the show around it. That’s why people still talk about where they were when “Purple Rain” met actual rain—why a halftime meant to bridge action became the action everyone remembers.

Years later, official uploads and retrospectives still circulate the performance, and each rewatch seems to gain weight rather than lose it. You know the notes that are coming; the shock is that they still feel inevitable and new. In an era when everything can be replayed and remixed to death, it remains the rare television moment that lives like a memory from a great concert—humid, unrepeatable, and charged with the hush that follows a perfect last chord. That’s not nostalgia; that’s craft meeting chance in real time.

So what made it special? Not just that a superstar triumphed over lousy weather. It’s that he alchemized it—folded rain into rhythm, risk into theater, coverage into communion. On paper, the halftime brief is impossible: be specific enough to be yourself and broad enough to move a continent. On that Miami night, Prince solved the equation with showman’s math and a meteorologist’s grin. The sky opened. The song answered. And for twelve minutes, the biggest event in sports paused to let music write its own forecast.

@80sdeennice Prince sings “Purple Rain” (in the rain) in the greatest Super Bowl halftime show of all time 💜 ☔️ When the producers approached Prince before the set to warn him about the rain, he responded, “Can you make it rain harder?” #GOAT #SuperBowlXLI #2007 #prince #80sicon #80s #genx #80smusic #ilovethe80s #80skid #halftimeshow #purplerain #foryoupage ♬ original sound – 80s Deennice