When Prince Commanded the Storm: The Super Bowl Halftime That Made It Rain Harder

Prince rolled into Dolphin Stadium on February 4, 2007, ready to take on America’s most-watched stage—only to find the sky determined to be co-headliner. The first Super Bowl to unfold beneath a steady, relentless rain turned the turf into a mirror-bright sheet that made producers wince and born showmen smile. Word rippled through the tunnels before kickoff: briefed on the worsening weather, Prince reportedly replied, calm as a surgeon, “Can you make it rain harder?” In an industry obsessed with control, he seized the one uncontrollable element and folded it into his art.

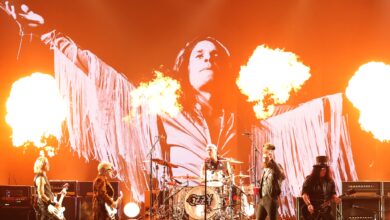

Officially, Super Bowl XLI featured the Indianapolis Colts against the Chicago Bears, yet by the long break the true drama was Prince against the storm. More than 74,000 spectators in fluttering ponchos surrounded a gridiron where a luminous stage—shaped like his iconic love symbol—would be rolled out by an army of volunteers, a neon vessel docking through wind and water. It was magnificent and perilous in equal measure: acrylic shine turns treacherous when soaked, and that night the platform resembled a wired skating rink. The crew wasn’t merely building a set; they were placing a bet on a daredevil.

Even the deployment of the platform played like a mini-thriller. Seventeen interlocking segments formed the love-symbol deck, edge-lit for broadcast clarity and engineered to assemble within minutes between plays. Volunteers drilled the choreography like a pit crew, and when showtime hit, they slid each piece into place with mechanical grace as rain sheeted down and the control room counted toward zero. In those cutaways you could almost hear the director’s pulse. This was live TV on high heat—and the headliner hadn’t taken the lift yet.

Then the elevator pushed him into view: turquoise suit blazing against pewter clouds, scarf knotted tight, posture unbothered by the gale. A thunderous tease of Queen’s “We Will Rock You” shook the stadium as fireworks cut white lines through the rain, and any fear that the weather would smother the moment evaporated. He lunged into “Let’s Go Crazy,” the Strat snarling as if the static in the humid air were a secret collaborator, while the audience answered every exhortation like a congregation. The infamous twelve-minute tightrope suddenly looked like his favorite balance beam.

What followed explained why booking Prince never counted as a conservative choice. He braided “Baby I’m a Star” and “1999” with Florida A&M University’s Marching 100, transforming the drenched field into a gleaming parade route. For television, reflective tape traced their formations, turning brass and drumline swagger into graphic spectacle. In lesser hands, a marching-band cameo might feel like easy applause. Here it read as purposeful pageant—another vivid stroke in a kinetic, fast-drying mural painted in rain and light.

Just as the audience settled into a greatest-hits sprint, he sidestepped into a different gear: reinterpretation. He fused Creedence Clearwater Revival’s “Proud Mary” with Bob Dylan’s “All Along the Watchtower,” shifting from bayou churn to apocalyptic folk-rock without dropping the thread. The transitions announced a musician who knows the architecture of the American songbook and isn’t afraid to remodel. The sequence played less like a medley and more like a thesis on lineage—how a Minneapolis original can conduct the nation’s jukebox with authority.

Then came the night’s boldest swerve: the Foo Fighters’ “Best of You.” On paper, the anthem seems far from his purple aesthetic. Under those lights, he treated it like a sanctified challenge, stretching the refrain—“Is someone getting the best, the best, the best of you”—until it felt primordial, as old as call-and-response under tent revivals. The choice, remembered as both cheeky and expansive, widened the halftime grammar. This wasn’t corporate sampler; it was a living mixtape spliced for thunderheads and broadcast delay.

All the while, the rain refused to fade into scenery. Droplets pearled on lenses; beams split into radiant veils; the stage gleamed like wet chrome. Where most artists would abbreviate their steps to protect balance, he leaned into spectacle—anchored stances, saber-like downstrokes, and crisp punctuation from The Twinz carving angles through the frame. What could have been a visual accident became an aesthetic decision. Instead of fighting the weather, the production learned to dance with it, and the results looked intentional, cinematic, inevitable.

Backstage nerves were justified. Mylar-slick flooring, high heels, and live current create a producer’s algebra of nightmares, yet safety calculations and star voltage found a truce. Reports from the truck recall frantic arithmetic—camera paths versus puddles, lightning graphics versus lightning risk—surrounding a performer whose center of gravity was absolute calm. The segment that later felt “effortless” to viewers came from dozens of people solving problems in real time while trusting an artist who thrived on volatility to hold focus.

For the finale, the legend and the meteorology fused. A translucent scrim lifted, lamps flared from behind, and the colossal silhouette of a guitarist—neck canted, stance inscribed like calligraphy—loomed through the weather as the opening chords of “Purple Rain” unspooled like prophecy. Because the storm was authentic, the purple wash turned the drizzle into vertical ink. Suddenly the metaphor became literal. People can debate the greatest halftime; few dispute that no ending has topped that backlit apparition in the downpour.

Inside the control room, technicians weighed lyricism against logistics—handhelds dodging spray, cranes carving clean arcs through vapor, switchers choosing glass that resisted beading. That millions experienced the moment as pure enchantment says everything about a crew that transformed hazard into texture. Wet fields rarely flatter live television. This one did because a virtuoso and a disciplined team agreed that weather wasn’t a problem to hide but a partner to feature, elevating risk into look and mood.

Context sharpened the achievement. In the years following the Janet Jackson incident, the league favored legacy names presumed “safe,” a programming instinct that traded surprise for predictability. Prince honored the brief—iconic, universal—while detonating the safety myth. By splicing Queen, CCR, Dylan, and the Foos into his own catalog, he reminded the widest possible audience that showmanship is a conversation with culture, not a museum tour. He didn’t merely satisfy a format; he reset what the format could dare.

Audience metrics sketched the scale: a national rating north of 40, peak viewership estimated above 90 million, and broader reach frequently cited around 140 million for the full broadcast. Numbers that large often sand down nuance, rewarding blunt gestures. He somehow threaded intimacy into a planetary frame, delivering close-read emotional beats within a wideshot circus. The game kept its headline, but the night’s imprint became twelve minutes where pop, funk, rock, and rainfall briefly formed an improbable supergroup.

Critical response arrived fast and calcified into consensus. Contemporary reviews placed the show among the greatest; retrospective lists keep it perched near or at the summit. Years of escalating halftime arms races—drones, augmented overlays, gravity-defying rigs—have not dimmed the allure of a turquoise suit, a love-symbol deck, and a storm no stage manager could script. The bigger the production gets, the clearer that night reads as rebuttal: give a genius a guitar and honest weather, and TV becomes cinema.

Even the set’s architecture traces a map of American music. Open with a Queen stomp to gather the tribe, sprint through Minneapolis groove, detour south with Fogerty’s churn, climb Dylan’s watchtower for apocalyptic resonance, test a modern arena anthem for gospel voltage, then close with a signature that under stormlight feels like fate. In a dozen minutes, he drew a lineage not from a distance but from within the bloodstream. The rain didn’t blur the lines; it underlined them in bold.

Ask veterans what single moment distills the night, and many cite that pre-show quip—“Can you make it rain harder?”—because it frames the entire enterprise. Entertainment often sells control; art often requires yielding to the unknown. Prince understood that mastery sometimes means embracing the uncontrollable and building architecture around it. That’s why people remember exactly where they were when “Purple Rain” met real rain—why a scheduled intermission became the main event seared into memory.

Time hasn’t sanded away the charge. Official uploads and anniversary features still circulate, and each replay seems to gain resonance instead of losing it. You anticipate the cues, yet the hits land as if inevitable and newly minted. In an age of infinite replays and algorithmic remixes, this remains the rare broadcast that breathes like a concert memory—humid, unrepeatable, punctuated by the hush that follows a perfect last chord. That isn’t nostalgia; it’s craft meeting chance under open sky.

So what made those twelve minutes singular? Not merely that a superstar persevered through miserable conditions, but that he alchemized the storm—converting rain into rhythm, risk into theater, coverage into communion. The halftime brief demands the impossible: be unmistakably yourself while moving a continent of viewers. On that Miami night, he solved the puzzle with showman’s calculus and a meteorologist’s wink. The clouds opened. The music answered. For one spellbound interlude, sports yielded so art could write the forecast.

@80sdeennice Prince sings “Purple Rain” (in the rain) in the greatest Super Bowl halftime show of all time 💜 ☔️ When the producers approached Prince before the set to warn him about the rain, he responded, “Can you make it rain harder?” #GOAT #SuperBowlXLI #2007 #prince #80sicon #80s #genx #80smusic #ilovethe80s #80skid #halftimeshow #purplerain #foryoupage ♬ original sound – 80s Deennice