When Halftime Became Home: Bad Bunny Turns the Super Bowl Stage Into Puerto Rico

The moment the stadium lights dropped at Levi’s Stadium in Santa Clara, the halftime show didn’t feel like a “break” in the game anymore. It felt like a hard cut into a new world, the kind of opening shot you’d expect from a big-budget film: Bad Bunny walking through a tall sugar cane field as if he’d stepped out of memory and into myth. The camera didn’t rush. It let the scene breathe. Dancers moved like field workers, the set looked lived-in instead of glossy, and the whole thing immediately signaled what the night was going to be: less about fireworks-for-fireworks’ sake, and more about building a place on the field where culture, pride, and pop spectacle could all exist at once.

From the jump, the crowd got exactly what they came for—energy, rhythm, and that instant-recognition roar when the first major hit landed. “Tití Me Preguntó” hit like the ignition switch, and suddenly the show’s pace snapped into gear. But what made it land wasn’t just the song choice; it was how the performance framed it like a homecoming party for an audience the Super Bowl hasn’t always centered. The choreography felt communal instead of clinical, like something you’d see at a street celebration rather than a sterile TV soundstage. Even through the TV, you could feel the field turning into a living block party, the kind of scene that makes people sit up on their couch and go, “Oh, this is one of those halftime shows.”

Then came the clever part: the show kept expanding without losing its center. Bad Bunny didn’t treat the stage like a single platform; he treated it like a neighborhood, with different corners that each meant something. One moment you’re in a field, the next you’re in front of colorful house-style set pieces that instantly read as a nod to Puerto Rican streets and family life. It wasn’t subtle, but it wasn’t empty either. Every transition felt like he was moving the audience through chapters rather than just hopping between songs. That’s the difference between a medley and a story: a medley is what you do to fit hits into a clock, a story is what you do when you want the world to feel your point of view.

A big chunk of the night’s impact came from the decision to lean fully into Spanish-language dominance on the biggest U.S. stage. Not as a gimmick, not as a “moment,” but as the default language of the show’s emotional engine. That choice alone changed how the performance landed. It wasn’t “crossover” energy—it was ownership energy. The show didn’t pause to translate itself for anyone. Instead, it trusted the audience to meet it where it was, and it trusted the music to do what music has always done at its best: communicate through feeling, rhythm, and sheer momentum. Even people who didn’t understand every word could understand exactly what kind of pride and intensity was being delivered.

As the set moved forward, the hits kept coming, but the show also made room for symbolism that felt pointed without turning preachy. You’d catch references that looked like they were built for replay—little Easter eggs meant to be screenshotted, debated, and explained in group chats later. That’s a halftime-show superpower: you’re not just performing live, you’re building a social-media afterlife in real time. When the production dropped in cultural cues—street-food visuals, neighborhood textures, and familiar Caribbean color language—it wasn’t just decoration. It was a way of saying, this belongs here too. This culture isn’t the side dish. It’s the main course tonight.

@iamchrisrodgers FULL BAD BUNNY SUPER BOWL PERFORMANCE!!!! #SuperBowl #badbunny #halftimeshow #halftimeshow2026 ♬ original sound – Chris

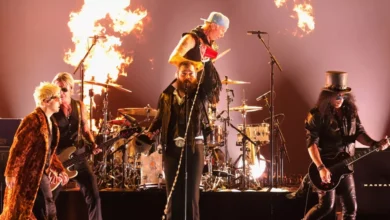

The guest appearances were handled like a flex, but not an insecure one. Instead of stacking celebrity cameos just to chase headlines, the show used guests as accents—big, loud accents that still made sense in the sentence. Lady Gaga’s arrival wasn’t treated like a takeover; it was treated like a moment of mutual respect, a pop-world handshake in the middle of a Latin-led spectacle. When a guest spot is done right, it doesn’t feel like the headliner needs help. It feels like the headliner is so in control that they can invite anyone into their universe and still keep the gravity centered on themselves.

Ricky Martin’s appearance carried its own kind of weight because it quietly stitched eras together. You could feel the lineage: different generations of global Latin stardom sharing the same field, in the same frame, on the same night. That matters because halftime shows are basically cultural time capsules. Years later, people don’t just remember the songs; they remember what the moment represented. Seeing a veteran icon step into a modern reggaetón-driven set didn’t feel like nostalgia bait. It felt like a statement that the story didn’t start this decade, and it won’t end with this headline. It’s a long arc, and this was one of those rare nights where the arc was visible.

What really kept the performance from becoming “just another huge TV production” was how often it returned to intimate human images. At one point, Bad Bunny handed a Grammy award to a young boy onstage, a visual that played like a symbolic passing of possibility—fame, validation, the idea that kids watching at home can picture themselves inside the dream instead of outside it. That’s not a typical halftime-show beat, and that’s why it sticks. The Super Bowl has always been about scale—bigger stages, bigger screens, bigger explosions. But the moments people replay for years are usually the ones that feel strangely small and personal inside all that noise.

There was also a noticeable effort to make the show feel like a place instead of a product. Some halftime performances look like they were designed by committee, built from brand-safe puzzle pieces. This one leaned into texture and specificity. Sets like “La Casita” didn’t feel like random props; they felt like anchors—visual shorthand for home, for community, for the kind of everyday life that rarely gets to be the headline on America’s largest sports broadcast. That sense of place gave the entire show a heartbeat. Even when the camera pulled wide and you saw the full scale, the vibe stayed grounded, like the spectacle was being powered by something real underneath it.

And then, because it’s the Super Bowl, the performance also understood the job: give people moments that explode. The choreography tightened, the staging started to feel like a controlled storm, and the crowd energy kept escalating as the set barreled toward its finale. “Yo Perreo Sola” landed with that unmistakable surge where living rooms turn into dance floors for three minutes. The performance wasn’t afraid of going full-pop, full-bright, full-loud. It just made sure that the loudness had a point. That’s a harder balancing act than it looks, and it’s why so many halftime shows feel huge but hollow. This one felt huge and intentional.

A key reason the night spread so fast beyond the broadcast was the way Apple Music built an ecosystem around it—before, during, and after. The “Road to Halftime” programming, the press conference, and the instant listening spikes turned the show into a multi-platform event rather than a single performance you watch once and forget. That kind of scaffolding changes how the culture experiences halftime. Instead of “watch it and move on,” it becomes “watch it, rewatch it, stream the set list, argue about your favorite segment, then watch the clips again.” Modern halftime dominance isn’t just about the 13 minutes on the field; it’s about owning the 48 hours after.

That afterglow was immediate. Listening behavior on streaming platforms is basically a real-time applause meter now, and the post-halftime surge told the story: people didn’t just enjoy the show, they went straight to the music. That’s the cleanest evidence of a halftime win—when the performance triggers a global reflex to hit play. The show wasn’t built to be an “advertisement” for the catalog in a cynical way; it was built to make viewers feel something strong enough that they needed more of it. When a halftime show does that, it becomes more than a TV moment. It becomes a consumption event, a cultural loop that keeps feeding itself.

By the time the finale arrived, the show had earned its closing message. The last stretch leaned into unity language—less “look how famous I am” and more “look how many of us fit under the same sky.” The phrase “Together we are America” played like a direct response to the way people try to shrink the definition of belonging. It was a simple line, but on a night that already looked like a celebration of Puerto Rican identity and Latin reach, it hit as a thesis statement. Not everyone wants politics in their halftime show, but halftime has always been political in its own way—through who gets centered, whose language gets heard, and whose stories get staged as worthy of prime time.

The fireworks did what fireworks are supposed to do—seal the memory with a visual stamp—and the closing song “DtMF” landed with that satisfying feeling of a performance ending on emotion rather than chaos. It wasn’t a messy “let’s cram one more hit in.” It was a deliberate descent into the kind of ending that makes people sit for a second before talking. That’s rare for halftime shows, which often finish like a sprint to beat the clock. This one felt like it finished with a final shot—an image you can freeze-frame and instantly remember where you were when you watched it.

In the bigger picture, what made this halftime show special wasn’t just that it was huge. It was that it was specific. It didn’t chase the broadest possible identity; it doubled down on a real one, and it trusted that authenticity to become universal through the force of performance. That’s the paradox of pop culture: the more honestly you represent something, the more people who have never lived it can still feel it. Bad Bunny didn’t water down his world to fit the Super Bowl. He expanded the Super Bowl to fit his world. And that’s why, years from now, people won’t describe it as “the year Bad Bunny performed.” They’ll describe it as the night the halftime show felt like a country’s heartbeat on the world’s biggest stage.