Black Sabbath’s 1997 Birmingham Reckoning: The Night Metal Stopped Asking for Permission

A few years before those hometown reunion nights, heavy metal still carried the same lazy insult in too many mainstream conversations: “it’s just noise.” The riffs were supposedly simple, the fans supposedly mindless, the whole genre supposedly a loud dead-end that serious critics tolerated at best and mocked at worst. And yet, anyone who actually traced the wiring of modern rock could see the truth hiding in plain sight: metal wasn’t a side quest—it was a foundation. By the late ’90s, the evidence was everywhere, from the way alternative bands leaned on down-tuned heaviness to the way stadium rock borrowed darkness for drama. The only thing missing was a single, undeniable moment where the genre’s originators walked back onto the stage and made the argument obsolete without saying a word.

That moment didn’t need a trendy city, a glossy awards show, or a “comeback narrative” written by publicists. It needed Birmingham—the industrial birthplace that shaped the band’s outlook in the first place, the kind of place where hard days and loud factories made soft fantasies feel dishonest. Black Sabbath weren’t just “from” Birmingham in the way bands list a hometown on a press kit. The city’s grit is in the DNA of their sound: the weight, the menace, the slow-motion dread that makes a single chord feel like weather. So when word spread that the original lineup—Ozzy Osbourne, Tony Iommi, Geezer Butler, and Bill Ward—were reuniting and bringing it home to the NEC in December 1997, it felt less like a tour stop and more like a reckoning that had been postponed for two decades.

The reunion had already been building heat earlier that year through Ozzfest, where Sabbath’s presence wasn’t some cute “special guest” cameo—it was a reminder of who wrote the blueprint everyone else was using. But Birmingham carried a different charge. This wasn’t the band returning to a market; it was the band returning to the source. And in 1997, that mattered because the culture was in one of those messy transition moments: grunge had burned through the early ’90s, Britpop had its own spotlight, and the new wave of heavy music was getting louder, more extreme, and more popular even as a chunk of the old guard still acted like it didn’t count. Sabbath’s hometown shows arrived like a receipt.

Outside the arena, you could imagine the vibe before a single note was played: generations stacked on top of each other. The fans who’d lived with these records since the ’70s weren’t arriving as casual listeners—they were arriving like witnesses. Meanwhile, younger heads were coming in with a different kind of intensity, because for them Sabbath weren’t just a band, they were the root system feeding everything heavy they loved. That blend is what makes a reunion either embarrassing or historic. If the old band looks fragile, the young fans get polite and the older fans get protective. If the old band looks powerful, the young fans go feral and the older fans feel vindicated. Birmingham 1997 didn’t drift toward nostalgia. It swung toward vindication.

Then the lights dropped, and the whole “noise” argument began dying in real time. Because the first thing a real Sabbath riff does—especially in a big room with a crowd ready to explode—is change the air pressure. It isn’t only volume. It’s authority. Tony Iommi’s guitar tone doesn’t behave like a normal rock sound; it lands like a heavy door closing. Geezer Butler’s bass isn’t there to politely underline the chords; it’s a second engine. And the drums—especially with Bill Ward back in the picture for those Birmingham nights—don’t just keep time. They swing, they push, they breathe. That’s what people miss when they call metal crude: the best metal isn’t stiff. It’s physical. It moves like something alive.

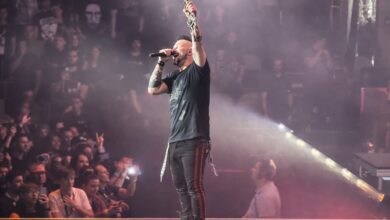

Ozzy’s entrance was the spark that turned the room from loud to volcanic. By 1997, he was already a solo superstar with his own mythology, but Sabbath Ozzy is a different creature—less ringmaster, more possessed storyteller. The second he starts working the crowd, you realize why these songs never stopped mattering: they’re built for call-and-response, for communal shouting, for an arena full of people turning a riff into a chant. This is where the “not real music” idea collapses first, because “real music” is the thing that unifies thousands of strangers into one voice. You don’t fake that with distortion. You don’t trick that out of a crowd. You earn it with songs that have lived in people’s bones for decades.

And those riffs… they didn’t sound like museum pieces. They sounded like instructions. “War Pigs” is the perfect example: it isn’t fast, it isn’t flashy, and it doesn’t need any modern trick to feel massive. The song marches. It accuses. It builds tension the way a storm builds pressure. In Birmingham, with a hometown crowd and the original lineup behind it, it lands as something bigger than a classic track—it lands as a public statement that heavy metal was always smarter than its critics claimed. The irony is brutal: some of the same people who dismissed metal as shallow also praised “political rock,” as if Sabbath hadn’t been writing about power, war, fear, and hypocrisy since the beginning.

As the set rolled on, the show started doing what the best reunions do: it reminded everyone that influence isn’t an abstract word. Influence is audible. When “Into the Void” or “Iron Man” hits in a room like that, you can practically hear the decades of bands that borrowed from those shapes—down-tuned weight, simple-but-immortal motifs, riffs that feel like architecture. It’s also where you see the band’s internal chemistry in the clearest way. Sabbath isn’t a “guitar hero plus backing musicians” situation. It’s a four-part machine. Iommi’s riffs create the structure, Geezer’s lines give it motion, Ward’s groove gives it swing, and Ozzy’s voice—odd, haunting, unmistakable—makes the whole thing feel like a message from a different world.

One of the most underrated thrills of those 1997 Birmingham nights is how the crowd becomes part of the instrument. Every chorus comes back like a wave, and not in the “sing along to the hit” way—more like a loyalty oath shouted with joy. That matters because it’s a direct rebuttal to the idea that metal fandom is purely about aggression. Yes, the music is heavy, but the emotion in the room is closer to release than rage. People aren’t screaming because they’re angry; they’re screaming because a part of their identity is being validated at full volume. When thousands roar the words back to Ozzy, it doesn’t feel like performance etiquette. It feels like history being confirmed out loud.

Then there’s the simple fact of how good the band sounded. Not “good for their age,” not “good considering it’s a reunion,” just good—tight where it needed to be, loose where it should be, and massive everywhere. That’s another way the “crude noise” narrative gets exposed. Crude music falls apart under scrutiny. Great heavy music gets better under scrutiny, because you start hearing the nuance inside the weight: how the drums lean, how the riff breathes, how a tiny pause before a chorus makes the whole arena jump a half-second later. Sabbath’s songs are full of these micro-decisions, the stuff that separates a riff from a moment. Birmingham 1997 wasn’t a band struggling to remember its lines. It was a band reminding everyone that they wrote the language.

At some point in a show like this, the realization hits that the reunion isn’t only emotional. It’s corrective. For years, Black Sabbath had been treated in some circles like a guilty pleasure that accidentally influenced “real” art. But standing in Birmingham with the originals in place, that hierarchy looks ridiculous. Because the music isn’t asking to be respected. It’s commanding respect by sounding undeniable. This is the difference between nostalgia and proof. Nostalgia is the feeling you get because you remember. Proof is the feeling you get because you can’t deny what you’re hearing right now. The riffs don’t care what anyone wrote in old reviews. They’re still standing.

And the hometown factor adds a layer you can’t manufacture anywhere else. Birmingham crowds don’t need to be convinced that Sabbath matters; they need to be given the chance to show what “matters” looks like when it’s personal. The city isn’t just cheering a band. It’s cheering an origin story. Four working-class kids from Aston who turned industrial gloom into music that conquered the planet—then came back home to confirm the victory on their own terms. That’s why the reaction feels “immediate and overwhelming” in a way that’s hard to replicate elsewhere. The audience isn’t treating the show like entertainment only. They’re treating it like a homecoming parade with amplifiers.

When the big closers arrive—songs like “Paranoid,” the kind of track that can turn an arena into a single bouncing organism—the night stops being a concert and becomes a communal event. This is where the “pillars” idea becomes obvious. A pillar isn’t a decoration; it’s a load-bearing piece of the building. You can paint the walls any color you want, but if the pillars go, everything collapses. Black Sabbath in Birmingham didn’t look like an old band trying to keep up. They looked like the structure underneath the whole thing. And the crowd response—instant recognition, word-perfect choruses, that roar that keeps rising—was the sound of a culture admitting what it already knew.

The proof didn’t end when the lights came up. Those NEC performances were captured and later released as the live album Reunion, which meant the moment wasn’t just a rumor or a “you had to be there” brag. It became a document: Sabbath, in their hometown, in late 1997, showing exactly what the songs sound like when the originals lock in and the audience treats every riff like a national anthem. Even the details underline the point—the recording dates, the venue, the lineup—because this wasn’t a vague “reunion era.” It was a specific, captured collision between legacy and present tense. A genre that had been dismissed for years suddenly had an official receipt stamped in Birmingham.

And that’s what makes those 1997 shows feel like a long-overdue reckoning rather than a sentimental reunion lap. Critics can argue about aesthetics forever, but they can’t argue with a crowd like that, or a band that sounds that powerful, or songs that still feel structurally inevitable decades later. Birmingham didn’t host a debate about whether heavy metal counted. It hosted the moment where counting stopped mattering because the foundation was visible. Black Sabbath didn’t plead their case. They played it. The riffs hit, the crowd shouted, and a whole history of dismissal folded up and vanished under the weight of one simple truth: this music built more of modern rock than anyone wanted to admit, and it was never going away.